Introduction

After 18 years in policy functions, I’ve watched the same skills crisis repeat itself with startling familiarity. Ministers change, initiatives launch with fanfare, millions are invested, yet we continue to have the same conversations we were having two decades ago. But this time, I genuinely believe we have an opportunity to break that cycle. However, only if we recognise that the skills crisis isn’t a single problem to be solved; it’s a complex, interconnected lifecycle that demands simultaneous action across every stage.

A crisis decades in the making

The skills challenge we see in so many sectors isn’t new, and frankly, that’s the most frustrating part. I’ve sat through countless policy meetings, strategic reviews, and industry roundtables over nearly two decades and the core issues remain remarkably consistent. The talent pipeline is thin. Careers advice is patchy. Young people don’t see our sectors as accessible or appealing. Businesses struggle to invest in training. Governments try to mandate solutions without understanding what industry actually needs. It’s a loop that has persisted through multiple administrations, each one believing their version of reform will finally crack the code.

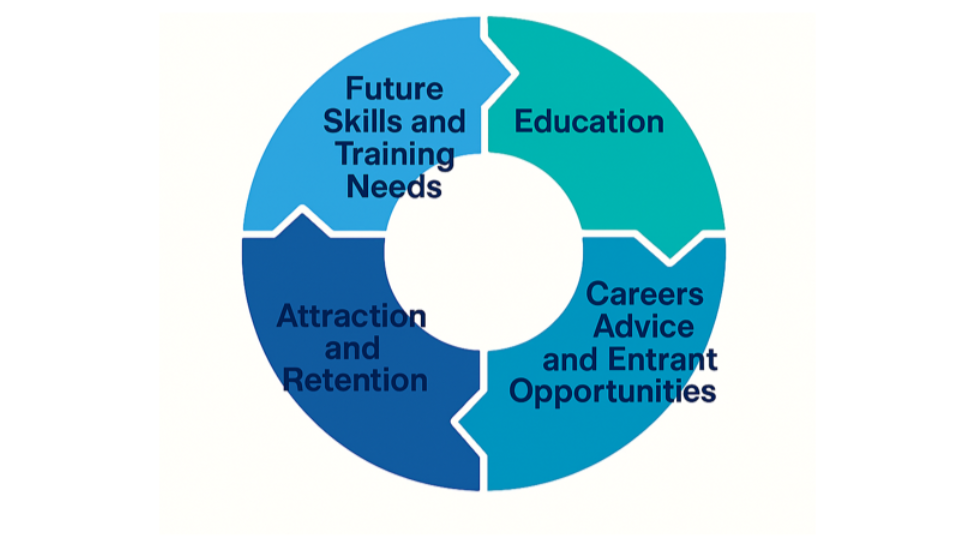

What’s different about this government, however, is both the scale of ambition and the recognition that something fundamental needs to change. The Skills and Growth Levy reforms, the record investment in education and training, the establishment of Defence Technical Excellence colleges for our sector, these are the most significant interventions I’ve seen in my career. But here’s the critical insight I’ve come to: these initiatives will fail if they remain isolated interventions rather than interconnected parts of a coherent system. That’s why I’ve developed the Skills Reforms Lifecycle framework to illustrate how every element of our skills challenge is intrinsically linked, and how success demands simultaneous action across all of them.

The four pillars of change

Starting early: making STEM engaging and relevant

The first and most crucial stage is education, and it must begin as early as possible – certainly well before young people make final career choices. By secondary school, most students have already mentally decided which subjects interest them and which don’t. For STEM disciplines, this is catastrophic for our sectors.

I’ve reflected on my own school experience: I was bored by maths. Not because I lacked capability, but because I couldn’t see the point. Finding x seemed abstract and disconnected from anything real. I simply didn’t understand why I’d ever need it. Now, imagine if my teachers had framed it differently. Imagine if they’d shown me that solving equations could literally help design the next aircraft, launch someone into space, or create technologies that transform the world. Past me would have sat up and paid attention. That’s the gap we need to close.

The challenge isn’t the curriculum itself – it’s how we teach it. The pedagogical approach to learning in primary and secondary schools has barely evolved despite technological revolution outside those classroom doors. We’re still asking children to answer questions in sequential, decontextualised formats rather than engaging them through narrative, challenge-based learning, and real-world applications. For sectors like ours, this is a pipeline killer.

If we’re going to succeed, we need education reformers and industry working hand-in-hand to inject relevance, storytelling, and tangible purpose into STEM teaching. When children understand that the physics they’re learning has real application in engineering, that computing skills open doors to innovation, that materials science underpins national security – engagement changes dramatically. And engagement is everything.

Navigating the careers advice maze

The second stage addresses what I call the careers advice conundrum, and honestly, it’s one of the most fixable problems we face. If we treat it like one.

I often use a slightly odd analogy, but it captures the frustration: in my local area, there are multiple parking apps, each one purporting to solve the same problem, each one fragmented and inconsistent. Why? It makes no sense. Yet this is exactly what we have with careers guidance. Schools offer advice inconsistently. Colleges have limited capacity. Parents often steer young people toward university by default, believing it’s the only credible pathway to a decent career, even when an apprenticeship or technical qualification would be far better suited. Meanwhile, young people in our sectors frequently don’t even know the opportunities exist.

What we desperately need is a single, integrated national platform, an “all singing, all dancing” digital solution that brings together: real vacancies across aerospace, defence, security and space companies; apprenticeship opportunities from entry-level to advanced and clear outlines of the various routes (university, college, on-the-job training, degree apprenticeships) available to reach specific career goals. This shouldn’t be a soft, advisory tool – it should be a working platform that young people and their advisers actually use because it’s comprehensive and current.

But platforms alone won’t fix this. We also need fundamental reform of the Skills and Growth Levy to provide genuine flexibility. And I mean genuine flexibility – not flexibility as governments imagine businesses need it, but flexibility as businesses know they actually need it. If a company identifies that it needs expert welders trained to aerospace standards, or digital specialists in cyber security, or advanced engineers in specific disciplines, they should be able to spend their levy on precisely that training regardless of course length, regardless of workforce size restrictions, regardless of whether it fits neatly into pre-approved categories.

When businesses can invest their levy in precisely the training gaps they face, and when young people have access to transparent, current information about career pathways, something fundamental shifts. The plumbing of the system starts to work.

Sector reputation and workforce attraction

The third pillar is one that industry itself must drive: making our sectors genuinely attractive places to build careers.

Businesses need to be acutely aware of three things. First, how their sector is perceived and where negative perceptions exist, they need to address them head-on rather than ignore them. If aerospace has a reputation for inflexibility or poor work-life balance, that’s a recruitment killer. If defence is seen as morally questionable by some demographics, that needs engagement, not denial. Second, what they have to offer future workers and here, the competition is genuine. Tech companies offer innovation and fast-paced change. Finance offers clear progression and bonuses. Our sectors need to articulate what’s unique and valuable about careers in aerospace, defence, security and space: the scale of challenge, the national importance, the technical sophistication, the tangible impact on security and innovation.

Third, they need to constantly monitor workforce trends and stay ahead of them. Flexible working, remote options, development opportunities, mental health support, diversity and inclusion. They’re baseline expectations. Sectors that don’t evolve their employment offering lose people. That attrition is as damaging as struggles in recruitment.

Anticipating the future

Finally, the lifecycle is only sustainable if there’s a constant lens toward what’s coming next.

The skills crisis will simply repeat itself on a 20-year cycle if we only address today’s problems. Right now, we’re struggling to find people with skills industry needs today. But in five, ten, fifteen years, the skill needs will be different. Emerging technologies, new materials, evolving defence capabilities, space sector expansion, digital transformation—these are reshaping what future workers will need to know and do.

Industry, government, and academia need to invest in genuine horizon-scanning. What are the emerging technologies that will define practice in our sectors? What new innovations could improve efficiency and capability? What skills gaps will exist in a decade? Once you’ve identified those answers, industry needs to work with government and educational institutions to build curricula that anticipate those needs. That’s how you break the cycle. That’s how we stop having this conversation in 2045.

Because if we don’t, we will see the same problems, the same frustrations, the same missed opportunities. A new generation of young people will be steered away from these sectors or won’t even know the opportunities exist. Businesses will compete desperately for talent. Skills shortages will drive up costs and constrain capability. We’ll blame education policy, or immigration policy, or business investment—and all the while, the real problem is that no one is seeing the system as genuinely interconnected.

A sector-wide challenge

I won’t pretend this framework captures every dimension of our skills crisis – it doesn’t. There are questions of social mobility, regional variation, the role of further education colleges, apprenticeship quality, industry investment levels, government funding mechanisms, and many others that sit within and across these four pillars.

But what this lifecycle does demonstrate is something I’m increasingly convinced of: there are no isolated solutions to the skills crisis. Education reform alone won’t work. Careers guidance alone won’t work. Attractive employer branding alone won’t work. Anticipatory skills planning alone won’t work. They have to work together, each one reinforcing the others, each one feeding into a coherent system.

That demands something genuinely difficult: industry, government, and academia genuinely collaborating rather than briefing against each other or pursuing separate agendas. It requires long-term thinking when political cycles are short. It requires patience when there are budget pressures. It requires accepting that quick wins don’t exist, but that a sustained, coordinated approach actually can transform outcomes.

Conclusion

To conclude, do you see this lifecycle in your own experience of the skills challenge? Where are we getting the interconnection right and where are we still treating these as separate problems? What would genuine collaboration across education, industry, and government actually look like in your part of the sector? And crucially, what’s stopping us from building it?

To learn more, I’d encourage you to join our Skills Working Group where we work through these crucial questions as a sector.